Introduction

South Africa is the land of my birth. As such, I have lived through many of the key events in South Africa; amongst them, the assassination of Prime Minister Vervoed, the Sharpeville massacre, the Soweto uprising, the transition to democracy, and much, much more. In this report, we will be starting from the beginning, and bring the entire geopolitical history to the current times, and also, what awaits the future of South Africa.

The Beginning

Starting in the mid-15th Century, European nations found their access to the goods of the east blocked by the establishment of the Ottoman Empire in the 1450s. To bypass this toll road, European navigators began exploring alternative routes to the east. One of them was via the Cape of Good Hope, a voyage around the southern tip of Africa, on route to India and China.

In the 1480s, Portuguese navigator Bartholomew is the first European to travel around the southern tip of Africa. Then, in 1497, Vasco da Gama lands on the Natal coast. This was followed by Jan Van Riebeck representing the Dutch east India Company, who founded the Cape Colony at Table Bay, Cape Town. In 1795, British forces seize Cape Colony from the Dutch. By 1810, the British were in firm control of the South African coast, and its key ports. The British were displacing other European colonial powers from various strategic areas around the world. This was the beginning of the rise to global power of the British Empire.

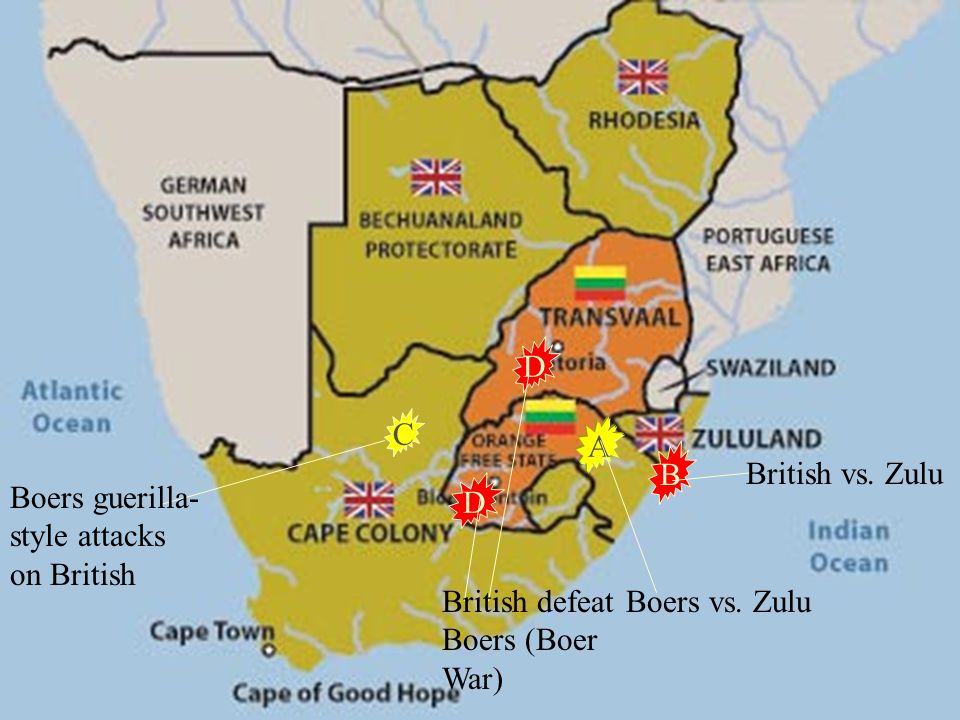

Between 1816 and 1826, Shaka, King of the Zulus, creates a formidable fighting force. Shaka had two nemeses: the Boer farmers and the British, both of whom kept on demanding territorial concessions from the local tribes. Shaka resolved to put an end to this land grab.

Similarly, the Boers (Dutch farmers) in 1835-1840, decided to leave the Cape Colony in the “Great Trek” and move northwards to found the Orange Free State and Transvaal.

Boers versus Zulu

1852 – British grant limited self-government to the Transvaal.

1856 – Natal separates from the Cape Colony.

Late 1850s – Boers proclaim the Transvaal a republic.

1860-1911 – Arrival of thousands of labourers and traders from India, forebears of the majority of South Africa’s current Indian population.

1867 – Diamonds discovered at Kimberley…with this discovery, the Jewish financiers in London sent their agents to take control of the diamond areas. Diamonds have been traditionally in Jewish hands for many centuries. The reason is as follows: – As we have seen, in Europe, during the Great Eviction period, when Jews had to flee, or were evicted, many times they had to leave their possessions behind. When this happened, these Jews fled with the most valuable and potable asset – diamonds. So, Jewish control of diamonds was built in to their genetic make-up.

1877 – Britain annexes the Transvaal.

1879 – British defeat the Zulus in Natal.

1880-81 – Boers rebel against the British, sparking the first Anglo-Boer War. Conflict ends with a negotiated peace. Transvaal is restored as a republic.

Mid 1880s – Gold is discovered in the Transvaal, triggering the gold rush. Unlike many other newly-discovered gold areas, South Africa had no need to borrow from the Rothschild banks to fund these ventures. Rather, the profit from the diamond fields helped to fund the gold-mines in the Transvaal. And since the British had annexed the Transvaal, and like diamonds, the Rothschilds controlled the international gold sector, even establishing the daily price of gold at N.M. Rothschild and Sons, in London. In essence, both the diamond and gold sectors came under British/Rothschild control from the onset. South Africa was becoming of increasing importance within the Rothschild/British Empire.

The Boers still controlled the Transvaal, and the British aimed to wrest political control away from the Boers. London gave instructions to effect a military takeover of the Transvaal.

1899 – British troops gather on the Transvaal border and ignore an ultimatum to disperse. The second Anglo-Boer War begins.

1902 – Treaty of Vereeniging ends the second Anglo-Boer War. The Transvaal and Orange Free State are made self-governing colonies of the British Empire.

1910 – Formation of Union of South Africa by former British colonies of the Cape and Natal, and the Boer republics of Transvaal, and Orange Free State. Now, here is where it gets interesting. Did you know that South Africa is the only country in the world with three capitals? Yes three! This is how it came about.

Although the British had now taken effective political control of South Africa, they had faced the toughest campaign in the history of the British Empire, in defeating the Afrikaners. So, in order to appease the Afrikaners, the British made Cape Town the legislative capital of South Africa. Why Cape Town? Because it was under firm British control. Then Pretoria was made the administrative capital of South Africa. This would leave the Afrikaners with some self-respect. And finally, the judicial capitol was in Bloemfontein, a compromise, and it was situated between Pretoria and Cape Town. Furthermore, it was part of the Afrikaner stronghold, Bloemfontein being in the Orange Free State.

1912 – Native National Congress founded, later renamed the African National Congress (ANC).

As the mining industry increased, a new problem emerged: sporadic shortages of labor. By the turn of the century, the system of recruitment and supply of mine labor that was to serve the mine owners so well for the next 75 years was firmly in place. In 1913, the Chamber of Mines (set up in 1889) by the mining houses to guarantee a regular supply of low-cost labor finally established control inside South Africa and the neighboring countries. With the shortage of labor worsening as more mines were sunk, the white mine workers wanted a rigid job color bar to protect their skilled jobs. Anxious to keep wage costs down, the owners decided to introduce blacks to lower-skilled jobs

1913 – Land Act introduced to prevent blacks, except those living in Cape Province, from buying land outside reserves. This was the first political move to establish apartheid, and it was initiated by the British, and not the Boers!

Most significantly, the Native Land Act of 1913 gave legal effect to the confinement of blacks to 8.8% of the land, establishing the permanent labor reserves that were later institutionalized as Bantustans. Finally, the Pass Laws regulated the entry of Africans into “white areas” to work. By creating the Native Land Act, the Jews and the British and the Rothschilds made sure that blacks were unable to farm on the 91.8% of the land taken from them. They could not farm. In order to feed their families, many, many of these Africans went to search for a job in the mining industry. Presto! The labor shortage was removed with this Act, in 1913.

From the last 4 articles on the Start of the Affair, we have shown how the idea of apartheid was first introduced on a systematic basis into mankind by the Levites in Judah, around 650 BC, with the production of Deuteronomy. This same racial bias has stuck with the Jews down the ages. In South Africa, it has now been proven, by the above, that the original idea of apartheid was first introduced by the Jewish mine-owners. Their aim was to have a large, surplus pool of labor to work in their mines and factories.

The majority of Africans were content to farm, but with the introduction of the Native Land Act, their land was stolen from them. Instead, they were confined to certain “reserves”, or bantustans. And the Pass Laws made sure that an African could not enter, on his own free will, into the 91.2 % of South Africa that was now deemed “white”. In short, apartheid was introduced to serve and benefit the Jewish interests.

And, when, in the late 1980s, this system had found to have outlived its usefulness, incredible pressure from both London and New York was applied to South Africa and the Afrikaner government to abandon the apartheid system. So, we can see that both the birth and death of apartheid in South Africa emerged from the same financial families. A look at the chronology will give us a somewhat clearer insight. In response to the British-initiated Land Act, the Boers in, 1914 founded the National Party.

As a result of the Anglo-Boer War, the Afrikaners became anti-British and anti-Jewish, and when the First World War broke out, there was much hope within Afrikaner circles that the British would lose, but Germany lost instead. During the Second World War, Afrikaner sentiment was very much pro-German, but-once again- the Germans lost. Nonetheless, three years later, the Afrikaner political party, the Nationalists won the elections and assumed political power in 1948.

Enter the Oppenheimer Family

Cecil John Rhodes was the principal Rothschild representative in southern Africa. With his death in March 1902, a replacement was desperately sought out. Natty Rothschild wanted a fellow Jew to head up the South African portfolio, as its importance in the overall scheme of things had, at this moment, become vital to the Rothschilds. This importance lay in 3 things: gold and diamonds, plus South Africa’s geographical position.

This search ended with the appointment of a fellow Frankfurt (Germany) resident. (Frankfurt was the birth place of the Rothschilds – and the Oppenheimers were living in the same Jewish ghetto as the Rothschilds), Ernest Oppenheimer. He, along with his brothers, worked for their cousins at the London-based firm of A. Dunkelsbuhler – diamond dealers. The five Oppenheimer brothers soon dominated the business. One brother, Louis, had become the firm’s Kimberly representative. Another brother Bernhard signed the 1890 diamond syndicate agreement, on behalf of Dunkelsbuhler, which created the first effort at setting up of a world diamond cartel. A few years earlier, the creation of De Beers was made possible with the help of a 5 m pound cheque from the Rothschilds (it was the largest single cheque written in the world up to that time). In fact, the London Rothschilds are still the secret power behind De Beers.

It was in this environment that the Oppenheimer brothers came to the attention of Natty Rothschild. After several meetings, Natty sent Ernest Oppenheimer to be his nominee in southern Africa. So, some 6 months after the death of Cecil Rhodes, Ernest arrived in South Africa, in November 1902. Within a short time, the Oppenheimer Empire grew, and it has not stopped growing, even up to the present moment.

1917 – The Rothschilds formed a company to hold their South African interests. This was called the Anglo-American Corporation. It was called Anglo-American, because the funding for this came from London and the Morgan Bank on Wall Street. The House of Morgan was the most powerful investment bank, at that time, in America, and it was an arm of the London Rothschilds. The Oppenheimer family was the Rothschild nominees in South Africa, and it was Ernest Oppenheimer and his progeny that ran this company.

1918 – Secret Broederbond (brotherhood) established to advance the Afrikaner cause 1919 – South West Africa (Namibia) comes under South African administration. This territory was previously a colony of Germany. With Germany’s defeat in 1918, the Allied Powers “gave” Namibia to South Africa.

Gold, Oil and Rival Empires

For well over a century, the ability of London to stand as the centre of international finance had depended on controlling the world’s physical trade of gold through London. London’s N. M. Rothschild & Sons set the world’s daily gold price at its bank, and their central bank, the Bank of England held the bulk of the world monetary gold. London had been successful because it had, first, captured the vast bulk of new gold discovered in California and Australia after the 1840s and later, out of the Boer War, it captured South Africa’s huge supply.

The British economy had undergone a 23-year economic slump, from 1873 to 1895, owing to a gold shortage. The depression had only ended when South African gold entered London. By 1925, South Africa’s gold mines produced half of the world’s gold annually, with the output increasing rapidly each year. Much of the history of the British Empire, and British foreign policy, from the 1850s through the 1920s, traced back to this subtle, little-appreciated manipulation of physical gold production flows into and out of the London gold market.

One consequence of the destructive World War 1 of 1914-1918 had been the massive transfer of Europe’s gold reserves out of European central banks and into the vaults of the Federal Reserve, as debt-strapped European countries were forced to pay for war-time supplies in gold. By the time the war ended, New York had become the owner of the vast bulk of the world’s monetary gold. Until the 1914 outbreak of war, gold had been the basis of the international financial system, a system that had been centered in London since the Napoleonic Wars (1805-1815), and controlled by the Rothschild family.

America, by this time, had come to be increasingly dominated by one family – the Rockefeller family. And they were not on good terms with the Rothschilds who controlled Europe’s finances, and, more specifically, the British.

The Rockefeller faction agreed that an emerging, informal American Empire, based on the dominance of US gold reserves and of the Wall Street banks, should ultimately replace Britain as the leading global power. All major Wall Street factions agreed that their future lay in extending highly profitable loans to Europe, Latin America, Japan and the rest of the world, areas that had been the province of London and the Rothschilds for nearly a century.

New York, and particularly the faction tied around the Rockefellers viewed Britain as a distinctively junior partner of their New York-centered system – something to which London and the Rothschilds were not about to accept. At the Versailles peace talks in 1919, Washington demanded that the Allied nations, particularly Britain, must repay their billions of dollars of war loans, it confirmed that America was no longer content to play a junior role. In a very real sense, the entire history of British geopolitics in Europe and the rest of the world from 1919 to 1939 (when World War 2 broke out), was a desperate attempt by the British to avoid being pushed into that subordinate role, and to maintain their imperial dominance.

The economic and political power of the British Empire had been severely damaged by the war and the huge debts it had brought about, but the Empire still formed an essential part of the world financial system. In 1919, London came off the gold standard, while New York came back on the gold standard. Along with the deletion of its gold reserves went London’s control over world credit, the heart of British geopolitical world influence.

The South African Threat

The looming danger for Britain, in addition to its war debts to America, was that South Africa would ship its future gold production to New York, rather than to London, making New York, not London the world’s principal gold market. That would rob the Bank of England of its most powerful weapon: control of world gold flows. The financial center of the world would shift from London to New York, with devastating consequences for Britain’s influence in shaping world events.

To prevent such a devastating result, London went to great lengths to exert control over South African government policy. London’s “ace” was South Africa’s Prime Minister in 1919, Jan Smuts, a member of Britain’s Round Table, an inner circle of Britain’s most powerful men, and a Rothschild entity.

Smuts had become South Africa’s Prime Minister in August 1919, just as Britain was forced to abandon the link of Sterling to gold. In April 1019, the Bank of England and South African gold mining companies signed an agreement whereby all South African gold will be shipped to London, and nowhere else. This appeared to give London continued exclusive control over South African gold output, and the ability to prevent direct South African gold shipments to New York. South Africa was the key to London’s future strategy of resuming its pre-war role at some future date, as the financial capital of the world.

The march of South Africa down London’s “yellow brick road” was abruptly interrupted in 1924. During the Great War (1914-1918), South Africa had been forced to link its currency to British Sterling, at a great economic cost to the domestic economy. By linking the Rand to Sterling and placing an embargo on gold sales other than to London, South Africa’s largest export earner, gold, suffered. Living standards of ordinary South Africans dropped sharply during the period when the gold standard was abandoned. Strikes of mineworkers demanding higher pay became frequent.

In early 1922, as the cost of living soared and the price of gold fell, mine owners threatened to replace white miners with black miners who would work for lower wages. The white miners called a general strike, which became known as the Rand Revolt and went on for three months. Smuts declared martial law and ordered brutal military repression, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of mine workers, and winning Smuts the nickname, “man of blood”. Having successfully pitted whites against blacks, the system of apartheid became a firmly entrenched policy of the South African government (still under British control). In 1924, this issue cost Smuts his re-election. Under such conditions, the South African mines placed a time limit on its agreement with the Bank of England, till June 1925.

Under Smut’s pro-British rule, London’s delaying tactic had not been hard. All that changed when Smuts lost the elections in June 1954. A new government comprising the Labour Party and the National Party headed by Afrikaner nationalist General Hertzog took office.

Once in office, one of Hertzog’s first acts was to create a commission on whether South Africa should break with Sterling and re-establish the South African Pound on an independent gold-backed basis. For the first time, London had not been consulted prior to a major South African gold decision. Instead of choosing someone from London to head the commission, to London’s alarm, Hertzog chose one of America’s leading gold and money experts, Princeton University professor Kemmerer.

New York’s Geopolitical Offensive

A William Kemmerer was an economics professor at a Rockefeller-funded university-Princeton. He acted on behalf of Wall Street and the Rockefellers in spearheading a move to put as many countries as possible onto an American-controlled gold standard. Alarm bells began to ring at the Bank of England and at N.M. Rothschild & Sons. An unanticipated threat to the strategic interests of the British Empire had come from South Africa, where Hertzog, in concert with Wall Street, was playing the vital supporting role.

Kemmerer suggested that South Africa go onto the gold standard by July 1925, with or without Britain. This would mean de facto an American-dominated gold standard. This would prove to be boost for the South African economy, as London knew only too well.

In January 1925, Hertzog’s government announced it was implementing Kemmerer’s recommendation, in full. In London, this was regarded as a cause of war, pulled off by the upstart Americans and holding the gravest implications for future British power. The only problem was that Britain was in no shape to wage war with anyone, least of all the United States.

Direct shipment of South African gold to New York would have dealt a devastating blow to the plans of London, and British financial institutions to rebuild their dominance after 1919. American intervention into South Africa, via Kemmerer and Hertzog-who was greatly helped by Wall Street to win the national elections-, not only dealt a blow to Britain, but also threatened to reshape the entire world credit system on Wall Street’s terms.

When one does research in the field of geopolitics, it is important to look at the world as a whole in exactly the same way both New York and London, and their respective elites view the globe. The interests of both families are global. Sometimes what happens in one part of the world has an effect in another part of the world. Likewise, in South Africa, and the fight to control its gold flows, was, for New York, a means to get their hands on something far more valuable – the newly discovered oil fields of northern Iraq. This is present day Mosul, and the Kirkuk region around it.

A consortium of Rothschild interests had formed the Turkish Petroleum Co, and London had pushed out the shares of both Germany and Turkey out of this company. The Americans were deliberately excluded from any participation in this. Despite tremendous pressure exerted on the Turks, the French, and the British, London refused to give in. This battle, legal and otherwise continued from 1921 till 1927.

In 1927, the TPC struck oil at Baba Gurgur well no 7, in October 1927. It was a super gusher, and the oil reserves were enormous. Present day estimates show that Kirkuk holds between 27-40 billion barrels of oil!

This was the main target of New York. The attack on London’s control of South African gold flows was well meant from Wall Street’s point. But, this changed in 1927. A peace treaty was signed between the two families to divide up the global oil market. Part of this resulted in the Americans obtaining a 40% stake in the TPC. The attack on the South African gold flows was called off.

1934 – The Union of South Africa parliament enacts the Status of the Union Act, which declares the country to be “a sovereign independent state”. The move followed on from Britain’s passing of the Statute of Westminster in 1931, which removed the last vestiges of British legal authority over South Africa. Britain was too weak to hold onto South Africa.

We shall continue this narrative in the next part, wherein we shall deal with the period of Afrikaner rule, from 1948-1994.

Dear Sam and Joe

I have been ravaging your content for nearly a week. Such a varying perspective.

I’m my recent travels, I have met with many Royal families from SA and have come to learn that Europeans were trading and integrated in SA from almost the first voyage around the tip and possibly further back.

I have seen a document published by Dept. Arts and Culture which I did not read fully but had sight of. My understanding is that SA history is being rewritten.

Specifically they had indicated that there is much detail missing here (below) between arrival and and JVR landing.

“In the 1480s, Portuguese navigator Bartholomew is the first European to travel around the southern tip of Africa. Then, in 1497, Vasco da Gama lands on the Natal coast. This was followed by Jan Van Riebeck representing the Dutch east India Company, who founded the Cape Colony at Table Bay, Cape Town. In 1795, British forces seize Cape Colony from the Dutch. By 1810, the British were in firm control of the South African coast, and its key ports. The British were displacing other European colonial powers from various strategic areas around the world. This was the beginning of the rise to global power of the British Empire.“