How Eurasia Will be Interconnected – BRI version 2.0

Xi had announced that Beijing will hold the 3rd Belt and Road Forum in 2023. The forum was initially designed to be bi-annual, first held in 2017 and then 2019. 2021 didn’t happen because of Covid-19.

The return of the forum signals not only a renewed drive but an extremely significant landmark as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in Astana and then Jakarta in 2013, will be celebrating its 10th anniversary. That set the tone for 2023 across the whole geopolitical and geoeconomic spectrum. In parallel to its geoconomic breadth and reach, BRI has been conceived as China’s overarching foreign policy concept up to the mid-century. Now it’s time to tweak things. BRI 2.0 projects, along its several connectivity corridors, are bound to be re-dimensioned to adapt to the post-Covid environment, the reverberations of the war in Ukraine, and a deeply debt-distressed world.

And then there’s the interlocking of the connectivity drive via BRI with the connectivity drive via the International North South Transportation Corridor (INTSC), whose main players are Russia, Iran and India. Expanding on the geoeconomic drive of the Russia-China partnership as discussed by Putin and Xi, the fact that Russia, China, Iran and India are developing interlocking trade partnerships should establish that BRICS members Russia, India and China, plus Iran as one of the upcoming members of the expanded BRICS+, are the ‘Quad’ that really matter across Eurasia.

Connectivity in West Asia

In West Asia, BRI projects will advance especially fast in Iran, as part of the 25-year deal signed between Beijing and Tehran and the definitive demise of the Iran nuclear deal – which will translate into no European investment in the Iranian economy.

Iran is not only a BRI partner but also a full-fledged Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) member. It has clinched a free trade agreement with the Eurasia Economic Union (EAEU), which consists of post-Soviet states Russia, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. And Iran is, today, arguably the key interconnector of the INSTC, opening up the Indian Ocean and beyond, interconnecting not only with Russia and India but also China, Southeast Asia, and even, potentially, Europe – assuming the EU leadership will one day see which way the wind is blowing.

So here we have heavily US-sanctioned Iran profiting simultaneously from BRI, INSTC and the EAEU free trade deal. The three critical BRICS members – India, China, and Russia – will be particularly interested in the development of the trans-Iranian transit corridor – which happens to be the shortest route between most of the EU and South and Southeast Asia, and will provide faster, cheaper transportation.

Add to this the groundbreaking planned Russia-Transcaucasia-Iran electric power corridor, which could become the definitive connectivity link capable of smashing the antagonism between Azerbaijan and Armenia.

In the Arab world, Xi has already rearranged the chessboard. Xi’s December trip to Saudi Arabia should be the diplomatic blueprint on how to rapidly establish a post-modern quid pro quo between two ancient, proud civilizations to facilitate a New Silk Road revival. And not only that; in parallel, the BRI gets a renewed drive, because the previous model – oil for weapons – will be replaced with oil for sustainable development (construction of factories, new job opportunities).

Apart from Michael Hudson, Credit Suisse analyst Poszar may be the only western economic analyst who understands the global shift in power: “The multipolar world order, is being built not by G7 heads of state but by the ‘G7 of the East’ (the BRICS heads of state), which is a G5 really.” Because of the move toward an expanded BRICS+, he took the liberty to round up the number. And the rising global powers know how to balance their relations too. In West Asia, China is playing slightly different strands of the same BRI trade/connectivity strategy, one for Iran and another for the Persian Gulf monarchies.

China’s Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with Iran is a 25-year deal under which China invests $400 billion into Iran’s economy in exchange for a steady supply of Iranian oil at a steep discount. While at his summit with the GCC, Xi emphasized “investments in downstream petrochemical projects, manufacturing, and infrastructure” in exchange for paying for energy in yuan.

In East Asia …

BRI 2.0 was also already on a roll during a series of Southeast Asian summits in November. When Xi met with Thai Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha at the APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) Summit in Bangkok, they pledged to finally connect the up-and-running China-Laos high-speed railway to the Thai railway system. This is a 600km-long project, linking Bangkok to Nong Khai on the border with Laos, to be completed by 2028. And in an extra BRI push, Beijing and Bangkok agreed to coordinate the development of China’s Shenzhen-Zhuhai-Hong Kong Greater Bay Area and the Yangtze River Delta with Thailand’s Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC).

To West Asia …

In the long run, China essentially aims to replicate in West Asia its strategy across Southeast Asia. Beijing trades more with the ASEAN than with either Europe or the US. The ongoing, painful slow motion crash of the collective West may ruffle a few feathers in a civilization that has seen, from afar, the rise and fall of Greeks, Romans, Parthians, Arabs, Ottomans, Spanish, Dutch, and British. The Hegemon after all is just the latest in a long list. In practical terms, BRI 2.0 projects will now be subjected to more scrutiny: This will be the end of impractical proposals and sunk costs, with lifelines extended to an array of debt-distressed nations. BRI will be placed at the heart of BRICS+ expansion – building on a consultation panel in May 2022 attended by foreign ministers and representatives from South America, Africa and Asia that showed, in practice, the global range of possible candidate countries.

Implications for the Global South

Xi’s fresh mandate has signaled the irreversible institutionalization of BRI, which happens to be his signature policy. Acute supply chain decoupling, the crescendo of western hysteria over Beijing’s position on the war in Ukraine, and serious setbacks on Chinese investments in the west all play on the development of BRI 2.0. Beijing will be focusing simultaneously on several nodes of the Global South, especially neighbors in ASEAN and across Eurasia.

From Beijing’s point of view, the stakes could not be higher, as the drive behind BRI 2.0 across the Global South is not to allow China to be dependent on western markets. Evidence of this is in its combined approach towards Iran and the Arab world. China losing both US and EU market demand, simultaneously, may end up being just a bump in the (multipolar) road, even as the crash of the collective west may seem suspiciously timed to take China down. The year 2023 will proceed with China playing the New Great Game deep inside, crafting a globalization 2.0 that is institutionally supported by a network encompassing BRI, BRICS+, the SCO, and with the help of its Russian strategic partner, the EAEU and OPEC+ too. No wonder the usual suspects are dazed and confused. The three main trade routes from East to West are as follows:-

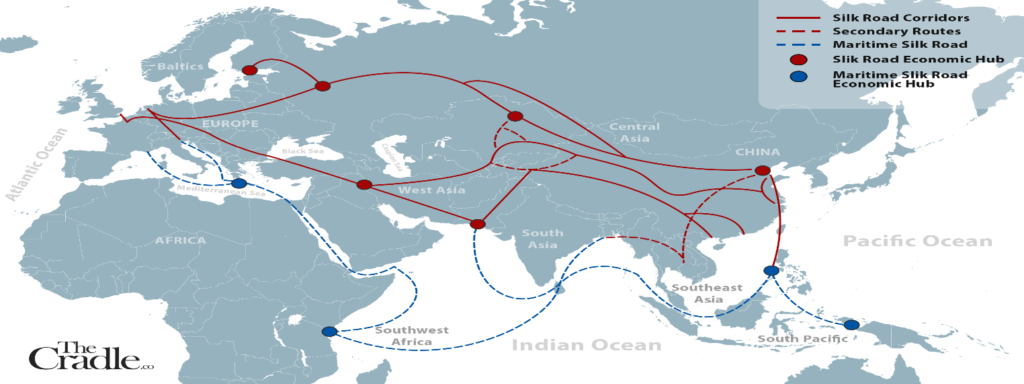

Map of BRI Corridors

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) gets its name from the Silk Road and consists of three corridors of development designed to promote trade and inter-civilizational commerce on an east-west basis.

The Three Arteries of the New Silk Road

- The Northern Corridor: Currently the most developed and utilized of the three corridors, it consists of railways and pipelines that run from China to Kazakhstan, Russia, and Europe. Some Atlanticist geopoliticians would like to see this corridor shut down to further isolate ‘new enemy’ Russia’s transportation and commercial routes.

- The Southern Corridor: Less developed but still important, this corridor involves the construction of continuous rail connections from China to Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and potentially Turkey, before reaching Europe through ports in Lebanon and Syria, and via land-based connections in Turkey. This route has the potential to promote sustainable peace and reconstruction in West Asian nations, and could possibly be extended to integrate and industrialize the Persian Gulf states through large-scale high-speed railway projects like the 2000 km Persian Gulf-Red Sea high-speed railway, and hasten development prospects in the strategic Horn of Africa.

- The Middle Corridor: These corridors are the Northern Corridor, the Southern Corridor, and the Middle Corridor. The most complicated but no less essential of these arteries is the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR), dubbed “the Middle Corridor” and features multimodal rail and sea transit of goods from China to Europe via Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, and Turkey. Although this path involves the shortest distance, complications and additional costs arise with the complex process of transitioning from land routes to sea routes via ports in the Caspian Sea. In recent months, the nations along the Middle Corridor have worked to harmonize their interests and coordinate their efforts to tap, process, and move the energy resources in the Caspian Sea (which contains the fourth largest natural gas reserves in the world).

The Importance of the INSTC

In addition to these three east-west corridors, the much anticipated Russia-Azerbaijan-Armenia-Iran-India International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) has also seen significant growth in recent years, with an additional eastern extension now stretching from Russia to Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Iran, and India.

Crucially, INSTC also happens to be an alternative to Suez. Iran, Russia and India have been discussing the intricacies of this 7,200 km-long ship/rail/road trade corridor since 2002. INSTC technically starts in Mumbai and goes all the way via the Indian Ocean to Iran, the Caspian Sea, and then to Moscow. As a measure of its appeal, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine, Oman, and Syria are all INSTC members. Much to the delight of Indian analysts, INSTC reduces transit time from West India to Western Russia from 40 to 20 days, while cutting costs by as much as 60%. It’s already operational – but not as a continuous, free flow sea and rail link. New Delhi already spent $500 million on a crucial project: the expansion of Chabahar port in Iran, which was supposed to become its entry point for a made in India Silk Road to Afghanistan and onward to Central Asia. What we see in play here is Iran at the center of a maze progressively interconnected with Russia, China and Central Asia. When the Caspian Sea is finally linked to international waters, we will see a de facto alternative trade/transport corridor to Suez.

The new architecture of 21st century geopolitics is already taking shape, with China providing multiple trade corridors for non-stop economic development while Russia is the reliable provider of energy and security goods, as well as the conceptualizer of a Greater Eurasia home, with “strategic partnership” Sino/Russian diplomacy playing the very long game. Southwest Asia and Greater Eurasia have already seen which way the winds are blowing.

Once goods from Russia reach Iran via either the western or eastern branches of the INSTC, they can be delivered to markets in India, South Asia, and East Africa through the Ports of Chabahar and Bandar Abbas on the Indian Ocean. The east-west BRI corridors and the north-south INSTC are highly synergistic and united in a grand strategic outlook for broad Eurasian growth and integration in a post-zero sum game world order.

On 20 December, Russia, Iran, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan released a joint statement offering all public and private interests across the globe a 20 percent discount on all freight transit costs for goods moving along the eastern branch of the INSTC. This discount would apply to all goods moving across the Middle Corridor (involving the Russia-Kazakhstan-China connection), as well as the eastern INSTC (involving Russia, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and China), and also the South-Eastern INSTC featuring Russia, Iran, West Asia, East Africa, India, and South Asia.

If Europe wishes to survive the coming decades, leadership will have to emerge that shrugs off the imposing pressures of the Anglo-American establishment, which seeks to stop the potential Europe-Russian-Chinese economic cooperation at all costs, even if it means the willful murder of millions of European citizens under an artificial imposition of energy scarcity, food scarcity, and war.

Nations of Central Asia and Southwest Asia have felt the burn of transatlantic imperial grand strategy for far too long and increasingly have come to recognize which pathway to the future is befitting their true interests – that of Eurasian integration.

Iran has already applied to become a member of the expanding BRICS+, which before 2025 will be inevitably configured as the alternative Global South G20 that really matters. Iran is already part of the Quad that really matters – alongside BRICS members Russia, China and India. Iran is deepening its strategic partnership with both China and Russia and increasing bilateral cooperation with India.

Iran is a key Chinese partner in the New Silk Roads, or Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). It is set to clinch a free trade agreement with the Eurasia Economic Union (EAEU) and is a key node of the International North-South Transportation Corridor (INSTC), alongside Russia and India. All of the above configures the lightning-fast emergence of Iran as a West Asia and Eurasia big power, with vast reach across the Global South. That has left the whole set of imperial “policies” towards Tehran lying in the dust.

So it’s no wonder that previously accumulated strands of Iranophobia – fed by the Empire over four decades — have recently metastasized into yet another color revolution offensive, fully supported and disseminated by Anglo-American media. The playbook is always the same. The extraordinary confluence between the signing of the Iran-China strategic partnership deal is bound to spawn a renewed drive to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and all interconnected corridors of Eurasia integration. This is the most important geo-economic development in Southwest Asia in ages – even more crucial than the geopolitical and military support to Damascus by Russia since 2015.

Multiple overland railway corridors across Eurasia featuring cargo trains crammed with freight are a key plank of BRI. In a few years, this will all be conducted on high-speed rail. The key overland corridor is Xinjiang-Kazakhstan – and then onwards to Russia and beyond; the other one traverses Central Asia and Iran, all the way to Turkey, the Balkans and Eastern Europe. It may take time – in terms of volume – to compete with maritime routes, but the substantial reduction in shipping time is already propelling a massive cargo surge. The Iran-China strategic connection is bound to accelerate all interconnected corridors leading to and crisscrossing Southwest Asia. Crucially, multiple BRI trade connectivity corridors are directly linked to establishing alternative routes to oil and gas transit, controlled or “supervised” by the Hegemon since 1945: Suez, Malacca, Hormuz, Bab al Mandeb.

Back to facts on the ground, the most interesting short-term development is how Iran’s oil and gas may be shipped to Xinjiang via the Caspian Sea and Kazakhstan – using a to-be-built Trans-Caspian pipeline.

That falls right into classic BRI territory. Actually more than that, because Kazakhstan is a partner not only of BRI but also the Russia-led Eurasia Economic Union (EAEU).

From Beijing’s point of view, Iran is also absolutely essential for the development of a land corridor from the Persian Gulf to the Black Sea and further to Europe via the Danube. It’s obviously no accident that the Hegemon is on high alert in all points of this trade corridor. “Maximum pressure” sanctions and hybrid war against Iran; an attempt to manipulate the Armenia-Azerbaijan war; Another fascinating chapter of Iran-China concerns Afghanistan- linking China to the Indian Ocean and the Black Sea. This is really serious business; a drive that may potentially link the Eastern Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean.

So everything will be proceeding interconnected: a Trans-Caspian link; the expansion of CPEC; Af-Pak connected to Central Asia; an extra Pakistan-Iran corridor (via Balochistan, including the finally possible conclusion of the IP gas pipeline) all the way to Azerbaijan and Turkey; China deeply involved in all these projects. Beijing will be building roads and pipelines in Iran, including one to ship Iranian natural gas to Turkey. Iran-China, in terms of projected investment, is nearly ten times more ambitious than CPEC. Call it CIEC (China-Iran Economic Corridor). In a nutshell: the Chinese and Persian civilization-states are on the road to emulate the very close relationship they enjoyed during the Silk Road-era Yuan dynasty in the 13th century.

Our next article deals with the geopolitics of the maritime chokepoints. This will answer many questions that have puzzled many for years.