BackGround

Since the story of the genocide of the Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar recently, calls have been coming in to do an article on this issue. To better understand the ongoing tragedy, it would help to understand some background.

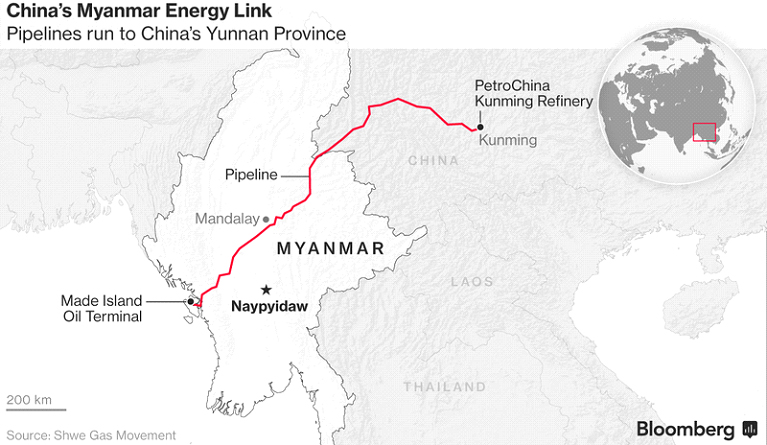

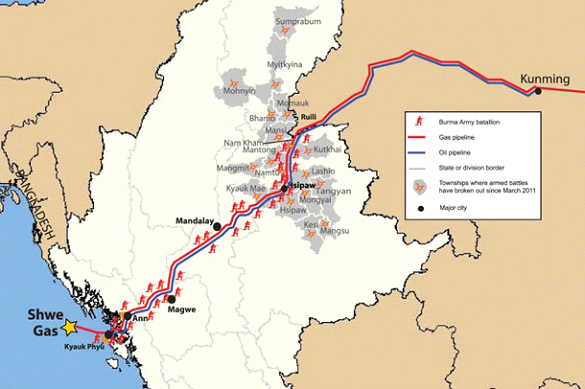

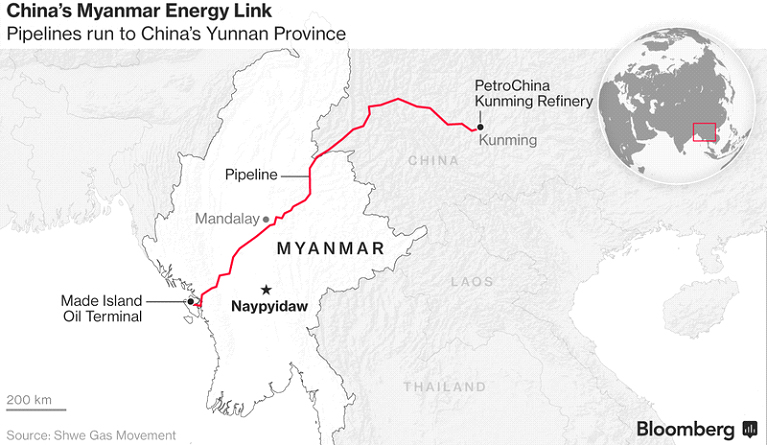

In early April this year, a 2,200 kilometer oil pipeline was supposed to flow oil as Myanmar opened a new deep water port at Kyaukphyu on the Indian Ocean. The project, officially begun in 2007 well before the strategic concept of a New Economic Silk Road was mature, is a vital part of China’s OBOR strategy. It consists of a US$2.45 billion port and pipeline project that will carry crude oil from the Middle East to China’s Kunming, the city near the border to Laos that is rapidly becoming a transportation cross roads in the Eurasian OBOR. The oil pipeline is a joint venture between China National Petroleum Corp. (CNOC) and Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise (MOGE), both state companies. The landing port in Myanmar’s Bay of Bengal has twelve storage tanks with capacity to store 520,000 barrels oil. When the oil pipeline is at full capacity, according to CNOC, the pipeline will be able to transport an estimated 400,000 barrels of oil per day from oil producers in the Middle East and Africa.

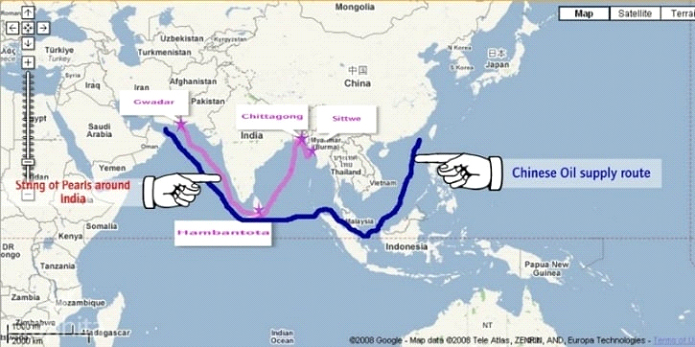

In geopolitical terms, the Myanmar-China port and pipeline will allow China to import oil from Persian Gulf producers as well as African, without having to take a far longer and militarily more risky route through the narrow Malacca Straits. The Malacca Straits, a narrow water passage is today the shipping route connecting the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean in the region of the South China Sea.

The Myanmar link will greatly shorten transport time and costs. The next phase of the new infrastructure corridor through Myanmar, the former Burma, will involve construction of a port for dry containerized and bulk cargoes, and a high-speed railway linking Kyaukphyu to Kunming, in Yunnan Province in central China. A modern industrial city of some 7 million people , Kunming is called by the Chinese the “City of Eternal Spring.”

The opening of the Kunming to the Indian Ocean pipeline is being called by oil analysts “one of the biggest developments of the decade for global crude flows.” It will allow China to receive oil from key producing centers like the Middle East and Africa directly off the Indian Ocean — eliminating days of sailing through the Strait of Malacca route between Indonesia and Malaysia.

Kunming, under the OBOR blueprint, will now become the hub and terminus for what will be called the “Pan Asia High Speed Network” with high speed trains to connect China, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore.

The vast multi-route Pan-Asia Rail Network when finished will efficiently integrate the economies of Southeast Asia with China for the first time creating huge new markets.

Why Myanmar Now?

A relevant question is why the US Government has such a keen interest in Myanmar at this juncture. The question is what would lead to such engagement in such a remote place as Myanmar?

Geopolitical control seems to be the answer. Control ultimately of the strategic sea lanes from the Persian Gulf to the South China Sea. The coastline of Myanmar provides naval access in the proximity of one of the world’s most strategic water passages, the Strait of Malacca, the narrow ship passage between Malaysia and Indonesia.

The Pentagon has been trying to militarize the region since September 11, 2001 on the argument of defending against possible terrorist attack. The US has managed to gain an airbase on Banda Aceh, the Sultan Iskandar Muda Air Force Base, on the northernmost tip of Indonesia. This was achieved shortly after the Asian tsunami decimated Aceh, in December 2004. The governments of the region, including Myanmar, however, have adamantly refused US efforts to militarize the region. A glance at a map will confirm the strategic importance of Myanmar.

The Strait of Malacca, linking the Indian and Pacific Oceans, is the shortest sea route between the Persian Gulf and China. It is the key chokepoint in Asia. More than 80% of all China’s oil imports are shipped by tankers passing the Malacca Strait. The narrowest point is the Phillips Channel in the Singapore Strait, only 1.5 miles wide at its narrowest. Daily more than 12 million barrels in oil supertankers pass through this narrow passage, most en route to the world’s fastest-growing energy market, China or to Japan.

If the strait were closed, nearly half of the world’s tanker fleet would be required to sail further. Closure would immediately raise freight rates worldwide. More than 50,000 vessels per year transit the Strait of Malacca. The region from Myanmar to Banda Aceh in Indonesia is fast becoming one of the world’s most strategic chokepoints. Who controls those waters controls China’s energy supplies.

That strategic importance of Myanmar has not been lost on Beijing.

Since it became clear to China that the US was hell-bent on a unilateral militarization of the Middle East oil fields in 2003, Beijing has stepped up its engagement in Myanmar. Chinese energy and military security, not human rights concerns drive their policy.

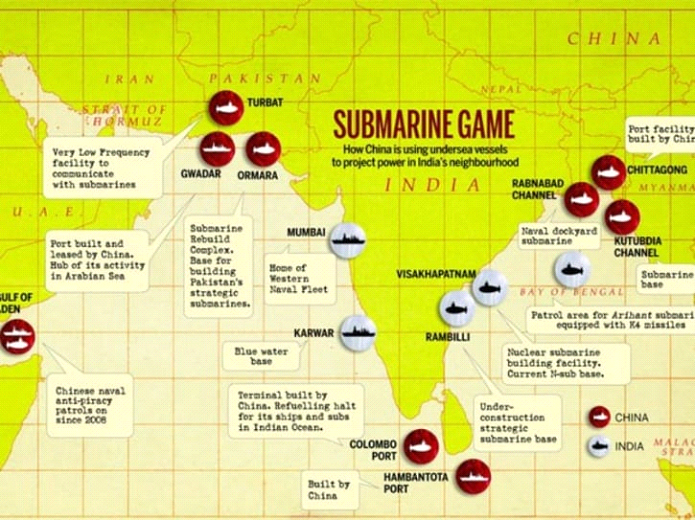

In recent years Beijing has poured billions of dollars in military assistance into Myanmar, including fighter, ground-attack and transport aircraft; tanks and armored personnel carriers; naval vessels and surface-to-air missiles. China has built up Myanmar railroads and roads and won permission to station its troops in Myanmar. China, according to Indian defense sources, has also built a large electronic surveillance facility on Myanmar’s Coco Islands and is building naval bases for access to the Indian Ocean.

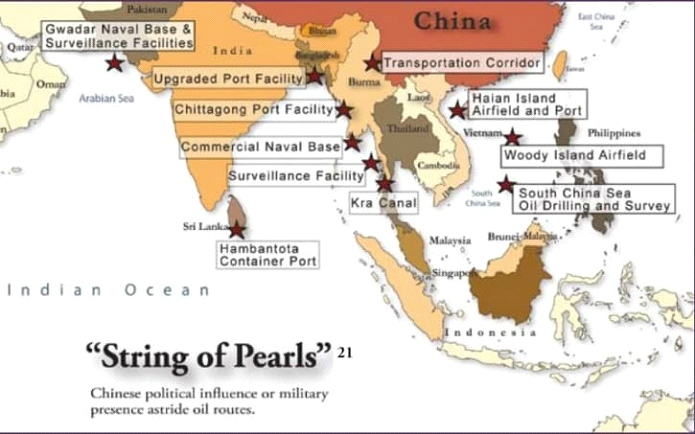

In fact Myanmar is an integral part of what China terms its “string of pearls,” its strategic design of establishing military bases in Myanmar, Thailand and Cambodia in order to counter US control over the Strait of Malacca chokepoint. There is also energy on and offshore of Myanmar, and lots of it.

With over 1.3 billion citizens and a fast-growing economy, China’s thirst for energy is rapacious. China has become the world’s largest energy consumer and producer and has overtaken the U.S. as the largest importer of oil on the planet.

The Gas Fields of Myanmar

Oil and gas have been produced in Myanmar since the British set up the Rangoon Oil Company in 1871, later renamed Burmah Oil Co. The country has produced natural gas since the 1970’s, and in the 1990’s it granted gas concessions to the foreign companies ElfTotal of France and Premier Oil of the UK in the Gulf of Martaban. Later Texaco and Unocal (now Chevron) won concessions at Yadana and Yetagun as well. Alone Yadana has an estimated gas reserve of more than 160 billion cubic meters with an expected life of at least 30 years. Yetagun is estimated to have about a third the gas of the Yadana field. In 2004 a large new gas field, Shwe field, off the coast of Arakan was discovered.

By 2002 both Texaco and Premier Oil withdrew from the Yetagun project following UK government and NGO pressure. Malaysia’s Petronas bought Premier’s 27% stake. By 2004 Myanmar was exporting Yadana gas via pipeline to Thailand worth annually $1 billion to the Myanmar regime.

In 2005 China, Thailand and South Korea invested in expanding the Myanmar oil and gas sector, with export of gas to Thailand rising 50%. Gas export today is Myanmar’s most important source of income. Yadana was developed jointly by ElfTotal, Unocal, PTT-EP of Thailand and Myanmar’s state MOGE, operated by the French ElfTotal. Yadana supplies some 20% of Thai natural gas needs.

Today the Yetagun field is operated by Malaysia’s Petronas along with MOGE and Japan’s Nippon Oil and PTT-EP. The gas is piped onshore where it links to the Yadana pipeline. Gas from the Shwe field is to come online beginning 2009. China and India have been in strong contention over the Shwe gas field reserves.

India Looses, China Wins

In 2012, Myanmar signed a Memorandum of Understanding with PetroChina to supply large volumes of natural gas from reserves of the Shwe gas field in the Bay of Bengal. The contract runs for 30 years. India was the main loser. Myanmar had earlier given India a major stake in two offshore blocks to develop gas to have been transmitted via pipeline through Bangladesh to India’s energy-hungry economy. Political bickering between India and Bangladesh brought the Indian plans to a standstill.

China took advantage of the stalemate. China simply trumped India with an offer to invest billions in building a strategic China-Myanmar oil and gas pipeline across Myanmar from Myanmar’s deepwater port at Sittwe in the Bay of Bengal to Kunming in China’s Yunnan Province, a stretch of more than 2,300 kilometers. China built an oil refinery in Kumming as well. During the past year an offshore gas facility pumped 1.88 billion cubic meters of gas to China.There are plans to build rail and road links along the same route as the oil and gas pipelines, establishing an economic artery that shortens transport times, avoids pirate-infested waters, and is, crucially, insurance against any future standoff with the U.S. over use of the Strait of Malacca.

Chinese economists revealed such fears ten years ago when they proposed the pipelines.

“Most of China’s oil imports come from the Middle East and Africa,” Li Chengyang, a co-author of the proposal, told the Straits Times in 2004. “Given the current situation in the Malacca Strait, we feel that we should come up with a suitable alternative. For China to fall under American control is a very risky thing.” “The old military government and the new are the same—they just changed their clothes,” he says, referring to the rise of a quasi-civilian administration in the 2010 election.

India’s Dangerous Alliance Shift

Ever since the Bush Administration decided in 2005 to recruit India to the Pentagon’s ‘New Framework for US-India Defense Relations, India has been pushed into a strategic alliance with Washington in order to counter China in Asia.

In an October 2002 Pentagon report, ‘The Indo-US Military Relationship,’ the Office of Net Assessments stated the reason for the India-USA defense alliance would be to have a ‘capable partner’ who can take on ‘more responsibility for low-end operations’ in Asia, provide new training opportunities and ‘ultimately provide basing and access for US power projection.’

As well, the Bush Administration has lifted its 30 year nuclear sanctions and to sell advanced US nuclear technology, legitimizing India’s open violation of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, at the same time Washington accuses Iran of violating same, an exercise in political hypocrisy to say the least.

US-backed regime change in Myanmar, which put Aung San Syu Kui into power, together with Washington’s growing military power projection via India and other allies in the region is clearly a factor in Beijing’s policy vis-à-vis Myanmar’s present military junta.

At independence, in 1948, Burma was the world’s largest exporter of rice and boasted one of the best universities in Asia. Half a century of tyranny and economic mismanagement have left the country splintered and impoverished.

The new government’s efforts at reform have earned muted applause from the U.S. and the EU, as investors line up to claim the country’s underground treasures—oil, gas, gold, timber, rare earth minerals, gemstones—and benefit from its cheap workforce.

Resource-hungry China filled the vacuum of foreign investment in Myanmar during the years of stringent Western economic sanctions, from the late 1990s until 2012, when most were lifted. At that time Myanmar officials, worried that their country could become a vassal state to China, began courting European and American interests as a way to balance foreign influence.

China’s “ String-of-Pearls”

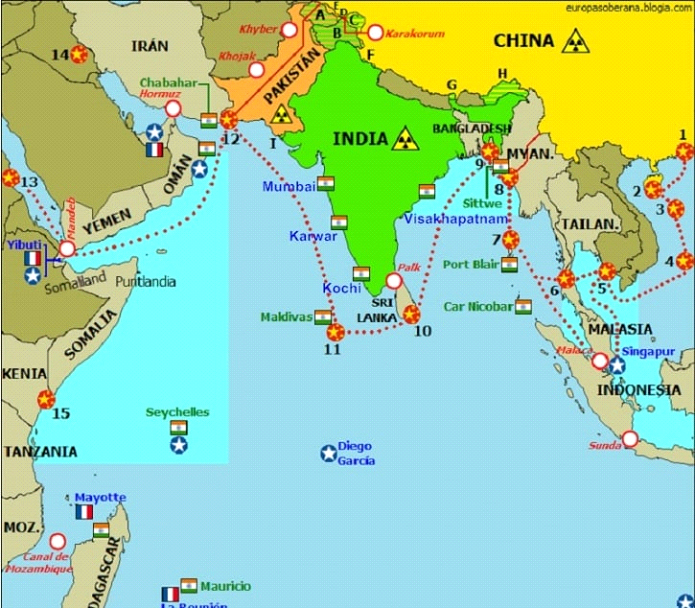

‘String of Pearls’ refers to a geopolitical theory to the network of Chinese intentions in India Ocean Region (IOR). Precisely, it refers to the network of Chinese military and commercial facilities developed by China in countries falling on the Indian Ocean between the Chinese mainland and Port Sudan.

China’s phenomenal economic growth began in 1979. At that time, China was self-sufficient in oil. By November 1993, China economy began growing at a faster pace, and it became a net importer of oil.

The US Navy controlled the sea lanes on which China depended, both for its oil imports as well as its manufactured exports. To avoid being blackmailed by the US, China decided to find alternative routes for its trading routes. With this in mind, it signed deals with Pakistan to establish a port at Gwadar, which eventually became the CPEC. With reports of China establishing a naval base in Pakistan, Washington may once again worry about the much talked about Chinese doctrine of ‘String of Pearls’ to evade the US Navy’s maritime footprint of in the region.

But first, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and now its macro form of One Belt One Road (OBOR) under which China will construct various land and maritime trade routes are also seen as a part of China’s larger military ambition.

China’s next “string of pearls” was established in Myanmar or Burma. This was followed by the Kra Canal project in Thailand. After many years of discussions, the Kra Canal has now received the official go-ahead from both governments. This happened in September 2017. We will discuss this in the next article on China; and finally, the port of Hambantota in Sri Lanka. These “pearls” are situated on the maritime routes between the Red Sea and China.

And finally, if all the maritime routes are blocked, China began to build transportation corridors inland, linking China to Europe, via high-speed railways, highways, ports and pipelines.

An idea originally brought out by economist Lyndon LaRouche in 1989, it was originally called “The Eurasian Landbridge”. China, in 2013, renamed it the “One Belt, One Road”, or OBOR, or the BRI. All of this, just to bypass the maritime chokepoint of the Malacca Straits.

Strait of Malacca

The Indian Ocean sees nearly 60 per cent of the trade which includes the trade of oil from the oil fields of the Middle East. And 80 per cent of China’s oil imports pass through the Strait of Malacca. Therefore, Strait of Malacca is indispensable for China until it develops alternative routes. Therefore China is keen to develop friendly relations with countries like Malaysia and Singapore which surround the Malacca Strait.

India has a strategic hold on Malacca Strait and in past as India had threatened to block Malacca Strait when China was mulling to help Pakistan in 1971 war. During the Kargil conflict in 1999, India had choked supply to Pakistan by using its navy-practically blocking the Karachi port. China is said to have developed a naval base near Strait of Malacca on Cocos Keeling Island, which is a distant part of Australia.

China has the presence in Myanmar’s Kyaukpyu port. The port situated in the Bay of Bengal has given China access to have a commercial Maritime facility which can be used as a military facility at the time of conflict.

Another main Chinese presence in close vicinity to Indian shores are at Coco Islands. Coco Islands are situated north of Andaman and Nicobar islands and strategically extremely important at the times of conflict. China is reportedly having a military base there as well.

Bangladesh

China has developed the port of Chittagong which again gives it a station to be used in the heart of the Bay of Bengal. China has invested a lot in Bangladesh and both Bangladesh and Myanmar are important points of OBOR’s sub-project, Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar (BCIM). China once again has been pushing Bangladesh to allow a naval base near Chittagong.

Sri Lanka

Though India has robust relations with Sri Lanka for centuries, China has found its feet in Sri Lankan soil as well. The Chinese company has developed a port Hambantota, in the Southern-eastern side of Sri Lanka and the Sri Lankan government has also allowed the control of it to a Chinese company.

The previous Rajapakshe government had allowed Chinese to build this port and it was likely to allow China to build a naval base here. But the Rajapakse government was ousted in 2015 election and the present Sirisena government has cordial relations with India, which seems to have given a jolt to the Chinese plans. Recently, the Sri Lankan government had rejected Chinese request of allowing one of its nuclear submarine dockings at Hambantota.

Pakistan

India relations require no introduction and China is Pakistan’s all weather ally. Therefore, Pakistan has always been China’s tool to keep India in check. The Gwadar Port developed by China for the purpose of CPEC is just the tip of the iceberg as the political pundits believe that China will not only assist Pakistan Navy through Gwadar port but would also launch offensive using this port in the scenario of a Sino-Indian conflict.

China hasn’t limited itself to lure the countries encircling India, but it has also made its presence felt on the African coast and the Middle East. China is said to have a powerful presence on the African coast of Indian ocean in Sudan and Kenya while it’s now building a military base in Djibouti to counter the increase American footprint in the Middle-East and IOR.

To counter Chinese influence in Myanmar, India has recently extended over USD 1.75 billion in grants and credit to Myanmar. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has recently visited Bangladesh and also received his counterpart in New Delhi. All these moves are seen as key to counter China.

In order to counter China’s Gwadar move, India has made deal with Iran and now India is developing Chabahar Port in Iran which is even more crucial than Gwadar as it’s located on the mouth of Hormuz strait from where oil trade from the oil fields in Saudi Arabia, Iran, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar and UAE takes place.

The Rohingya Issue

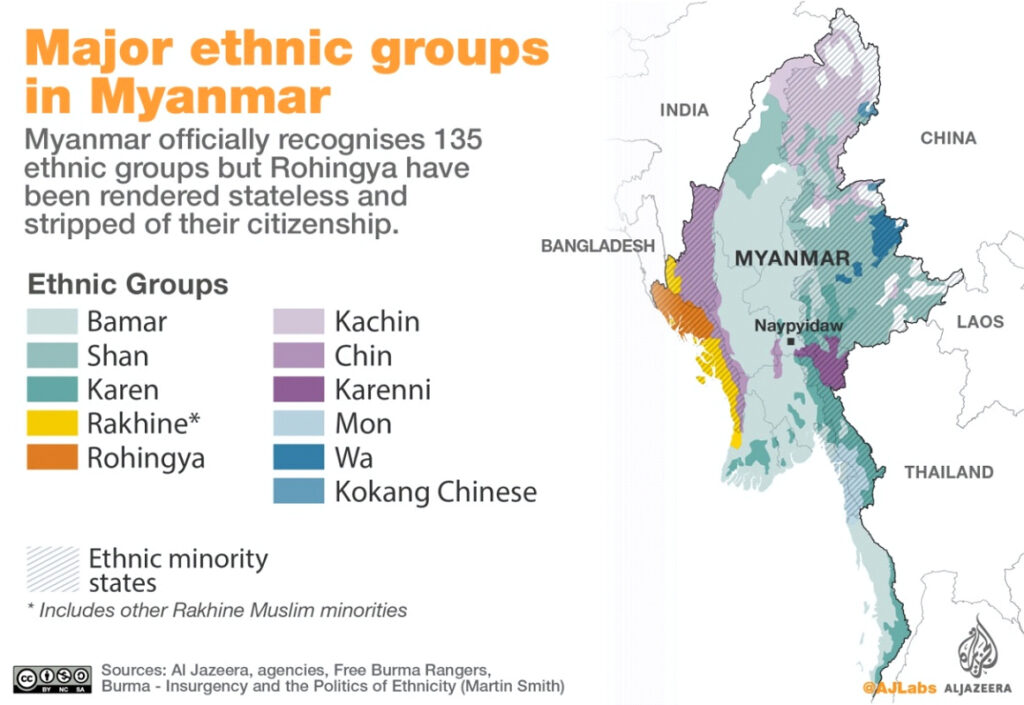

The Muslim Rohingya has been fleeing from Myanmar (Burma) by the thousands. The Rohingya are a minority ethnic group located in Myanmar’s western Rakhine state and are considered to be a variation of the Sunni religion. Since the Rohingya are considered to be illegal Bengali immigrants and were denied recognition as a religion by the government of Myanmar, the dominant group, the Rakhine, rejects the label “Rohingya” and have started to persecute the Rohingya. The 1982 Citizenship Law denies the Rohingya Muslims citizenship despite the people living there for generations. The Rohingya are fleeing Myanmar because of the restrictions and policies placed by the government. The restrictions include: “marriage, family planning, employment, education, religious choice, and freedom of movement” and they are facing discrimination because of their ethnic heritage. The people in Myanmar are also facing wide spread poverty, with more than 78 percent of the families living below the poverty line. With most of the families living below the poverty line, tensions between the Rohingya and the other religious groups have exploded into conflict. The violence and turmoil began in 2012, the first incident was when a group of Rohingya men were accused of raping and killing a Buddhist woman The Buddhist nationalists retaliated by killing and burning the Rohingya homes. People from all over the world started calling this crisis and bloodshed “campaign of ethnic cleansing.” The Rohingyas were placed in internment camps and today there are still more than 120,000 still housed there The Rohingya people have been facing persecution for their religion and as of today still have no rights or citizenship in their homeland.

The map will show the path of Rohingya from their ethnic homeland of Rakhine state in Myanmar to Bangladesh’s district of Cox’s Bazar, as well as several other countries in Asia, where the Rohingya have sought sanctuary since the 1970s.

Like so many other cases of ethnic cleansing, the Rohingya conflict is essentially a conflict over resources, namely oil and gas. In 2004, a massive natural gas field, named Shwe in honor of the long-time leader of Myanmar’s military junta, was discovered off the coast of Myanmar in the Bay of Bengal. In 2008, the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) secured the rights to the natural gas and bestowed upon the field its honorific name.

Construction began a year later on two 1,200 km overland pipelines that would cross from Myanmar’s Rakhine state – home of the Rohingya – to the Yunnan province of China.

The pipelines — one carrying gas and the other carrying oil from the Middle East and Africa, brought to Myanmar by ship — missed their targeted dates for completion. The gas pipeline became operational in 2014 and carries more than 12 billion cubic meters of natural gas per year to China. The oil pipeline has proven more difficult to construct and was completed earlier this year. This will allow China easier access to oil from the Middle East and Africa and will reduce the transport time of such oil by as much as 30 percent.

Beyond the obvious boon of having increased and easier access to oil, the Shwe oil pipeline is of critical strategic importance to Chinese geopolitical interests. Currently, 80 percent of China’s imported oil passes through the straits of Malacca and disputed parts of the South China Sea. This current route would leave China vulnerable to a potential energy blockade imposed by the 6th Fleet of the U.S. Navy, were hostilities to arise between the two rival nations. Once the Shwe oil pipeline became operational, the Chinese would no longer have to worry about the possibility of the U.S. imposing a blockade on the vast majority of Chinese oil imports, a critical advantage for China during a period of rapidly decaying Sino-U.S. relations.

Since construction began, protests against the pipelines in Rakhine state and other areas of Myanmar have been constant. Residents of Rakhine state, in particular, have complained to the government and to CNPC on numerous occasions that the project had polluted rivers, destroyed private property and decimated the livelihood of local fishermen.

The Myanmar government is a major stakeholder in the pipeline, as it owns a major stake in the Shwe field’s production of natural gas and is set to earn $7 million per year in annual right-of-way fees for the pipelines once both are completed. Given that public opposition forced Myanmar to suspend China’s Myitsone Dam project in Kachin state in 2011, the government is acutely aware that unchecked local resistance to the pipelines could potentially deprive it of millions of dollars in annual revenue. Thus, Myanmar’s military has been ardently pursuing the Rohingya, citing vengeance for periodic attacks launched by regional insurgents as a pretext for the violence that has forced hundreds of thousands from their homes.

The “Rohingya insurgency” in Rakhine state is hardly the organic, local response to long-standing state suppression it claims to be. The group, now known as the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) and formerly known as Harakah al-Yakin, is led by Ataullah abu Ammar Junjuni, a Pakistani national who worked as an imam in Saudi Arabia prior to arriving in Myanmar. According to a Reuters report from last year, the group is financed by “a committee of 20 senior Rohingya emigres,” headquartered in Mecca, which “oversees” the group.

ARSA is directly responsible for both last year’s and the current crackdown on Rohingya civilians and communities, as its attacks on Myanmar military installations and bases have precipitated the military’s violent response. ARSA has also targeted Buddhist civilians in Rakhine state, fomenting support among extremist Buddhists elsewhere in the country for the continued persecution of the Rohingya.

US Noncommittal Response a Product of its Long-Game Cynicism

U. interest in Myanmar is hardly new, as the US government, along with various US nongovernmental organizations, have spent millions on “democracy promotion” — specifically on funding the National League for Democracy (NLD) led by Suu Kyi. In 2003, a document titled “Burma: Time for Change” by the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) noted that the NLD, and its leader, “cannot survive in Burma [Myanmar] without the help of the United States and the international community.”

In the years since, the U.S. government has spent hundreds of millions of dollars in order to cultivate “democratic institutions” and spur “economic development” in order to push for a new form of government in Myanmar. Between 2012 and 2014, the Obama administration gave $375 million to Myanmar for such efforts.

Furthermore, in 2015, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) was the “leading donor” in Myanmar’s 2015 election, which saw Suu Kyi and her party claim decisive victories. It also funded the creation of Myanmar’s entire voter database that year and the use of all technology used in the election and subsequent elections. Ultimately, over $18 million was spent on the election by USAID.

Suu Kyi’s election marked a reversal for Myanmar in several ways, particularly economically. While Suu Kyi’s predecessors had favored investment from China and South Korea, Suu Kyi’s rise to power has seen increased U.S. investment in Myanmar, partly because the U.S. waited to remove sanctions against the country until she became the nation’s leader. Soon after her election, U.S. investment increased precipitously and is expected to double its current level by 2020. As of last month, U.S. companies had invested $250 million in Myanmar following Suu Kyi’s assumption of power.

However, this new surge in investment is not as new for U.S. oil and gas companies, who have been allowed to invest in Myanmar, despite U.S. sanctions, since 2012. The Obama administration made the exception due to the fear that the U.S. “would lose out to foreign competitors” before sanctions were fully lifted, a clear allusion to the Chinese and South Korean companies which had claimed large swaths of the Shwe gas field a year prior. However, Suu Kyi’s rise to prominence led to more lucrative contracts for U.S. and Western companies, particularly Shell Oil and Conoco Phillips.

While the uptick in U.S. corporate investment and U.S. ties is unsurprising given the U.S.’ own massive investment in Suu Kyi and her political party, the U.S. is less than pleased with Suu Kyi’s tenure thus far.

For instance, Suu Kyi has visited Beijing twice since becoming Myanmar’s leader yet has rejected an invitation to a conference organized by U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. She has expressed her feelings that China “will do everything possible to promote our peace process,” referring to China’s eagerness to end sectarian fighting in Rakhine State and other area of Burma. There are also suggestions that the Chinese are seeking to develop a naval base in the port city of Kyaukpyu, something the U.S. desperately wants to avoid.

Suu Kyi’s decision to keep China close is similar to the stance taken by Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte, who has fought to diminish the U.S.’ historically strong influence in his country and forge closer ties to both China and Russia. Interestingly, following the strengthening of ties between these two nations and China, Myanmar and the Philippines became the only Southeast Asian nations forced to battle against CIA-funded insurgencies — ARSA in Myanmar and Daesh (ISIS) in the Philippines. Duterte has implicitly blamed the U.S. for the rise of Daesh in his country.

The rise of both groups has offered a convenient excuse for the U.S. to boost its military presence in both nations. The U.S. is set to further expand its direct military ties with the Myanmar. It would also open the path for the U.S. to establish a military base, which would definitively end Chinese hopes for its own naval base in Myanmar. Meanwhile, Israel, a strong ally of the United States, has continuously been selling arms to Myanmar’s military.

With calls for Suu Kyi to take drastic action to address the issue growing by the day, the U.S. has the ability to force her hand, both covertly and overtly. If the crisis continues to worsen, the possibility that Suu Kyi will request U.S. military assistance to combat an outbreak of “terrorism” will grow. Such an outcome would greatly benefit the U.S., which would gain a new military foothold in another Chinese border nation and also secure Myanmar’s oil and gas riches for itself.

U.S. strategic interest in Myanmar is hardly limited to dominating the exploitation of the nation’s lucrative oil and gas resources. A large part of the U.S. motivation to wrest influence from the Chinese is crucial to its larger regional “China containment” strategy — one that seeks to create a united front of U.S. influence surrounding China in order to reassert U.S. dominance in the region.

This goal was notably expressed by former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton who, in a private speech in 2013, stated “we’re going to ring China with missile defense. We’re going to put more of our fleet in the area.” This policy has been put into practice with Obama’s 2011 “pivot to Asia” — resulting in a massive increase in U.S. arms sales to countries neighboring China.

With so much to be gained in geopolitical goal-realization from a favorable veer in the current “crisis,” the U.S. is also acutely aware of what it stands to lose if the chips fall the other way. The opening of the Shwe oil pipeline to China would permanently remove the US’s capacity to impose a blockade on 80 percent of China’s oil supply. Losing this massive strategic advantage would be disastrous for the U.S. were a major geopolitical conflict between the two rival powers to develop. With the U.S. threatening to remove China from the SWIFT banking system, tensions on the Korean peninsula flaring, and China touting an oil/gold/yuan alternative to the petrodollar, such a conflict is far from a remote possibility. Thus, the U.S. interest in Myanmar is multi-faceted — a sinister union of the U.S.’ ever-growing demand for fossil fuels and its ruthless push to reassert political dominance in Asia at China’s expense.

Ultimately, the Rohingya are the latest pawns of the United States’ desperate attempts to cling to global dominance under the guise of “humanitarianism.” If U.S. interests are successful and oust the Chinese, the Rohingya will continue to suffer all the same. The only difference will be that their tormentors will answer to different masters.

Timeline

2007: Agreement signed between Myanmar and China on the construction of a transportation corridor from Sittwe to Kunming. Construction starts not long after.

2012: Chiina beats India over the concession for the Shwe gas field in Myanmar.

2014: Just as the Shwe gas pipeline comes online, the CIA initiated a series of armed attacks ARSA, thus inviting retaliation from the Myanmar military.

2017: the new oil pipeline has been completed. The refinery in Kunming that is to receive this oil was completed, and was awaiting crude oil to begin refining operations.

April: The Suezmax tanker United Dynamic arrived at Myanmar around April 9 after loading oil from the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan terminal in Turkey on March 5. PetroChina finished building the refinery in the provincial capital Kunming about six months ago and has been waiting for pipeline deliveries to start. It will take about 12 million barrels of crude to fill the pipeline before deliveries can start.

A while back, the launch of the oil pipeline had been postponed again despite talks of imminent start-up, because the project was awaiting final approvals and permissions for tankers to enter Myanmar waters. PetroChina and Myanmar’s government had yet to finalize the deal for the pipeline set to carry oil across Myanmar to the landlocked southern Chinese provinces neighboring Myanmar. In addition to this finalization hurdle, PetroChina had not yet obtained permission from Myanmar’s Navy for tankers to enter ports in the country, according to Reuters’ government source familiar with the matter.

The $1.5-billion oil pipeline—conceived some ten years ago and completed late in 2014—has not been used due to strained relations between Myanmar and China and its inability to obtain final authorizations. Petro China was “trying to push to get the permission from the navy to enter Myanmar water”. The crude is to be supplied to Petro China’s brand new refinery in the Yunnan province, where test production is scheduled to start in June.

According to shipping data by Thomson Reuters Eikon, the supertanker that has been chartered to ship the first oil for the Myanmar-China pipeline from Azerbaijan has been sitting offshore Sri Lanka.

August: China signed an agreement with Myanmar to supply electricity, as Myanmar is desperately short of electricity. Half its population does not have access to electricity. The Chinese-financed dam at Myitsore, was cancelled in 2011, due to American pressure. This would have solved Myanmar’s electricity deficits. In order to avoid the activation of this oil pipeline, the CIA, once again, activated the ARSA militia.

On the 25th, ARSA launched a well-coordinated attack on 25 police stations and checkpoints in the Rakhine State. The CIA knew full well that this would provoke a military response from the Myanmar government. And that is precisely what happened. The resulting turmoil in the province has, for now, put any oil flowing through this pipeline on hold.

America cannot allow this pipeline to function. At the same time, America has launched a media and diplomatic war over North Korea. Just by looking at the map, one can see that China is being targeted now from 2 directions – North Korea and Myanmar; in addition to Taiwan and Japan.

With the soon-to-be-launched oil exchange in Shanghai, using gold-backed yuan, China is truly poking the American bear. A Petro-Yuan, and a safe, secure new oil pipeline, China would be in a strong position financially. Will America and the Rockefeller Empire allow this? We live in interesting times, indeed.

Thanks a million Sam, for a great and most detailed write-up on this tremendously important topic. Now that makes sense why Aung San Suu Kyi was abandoned to her fate by the Anglo-Americans. They thought they could play her like a puppet, but deep down, as much Westernized as she is, she’s still a nationalist at heart, reflected by her openness toward China for the sake of her people.

Could you also write on the geopolitics situation of VietNam and Thailand (including historical background) when you find the time? I think these 2 countries are also important (and are becoming more important in the next 10-15 years) to know more about. I’m a Vietnamese, but I’ve never found any source of info like this on my country anywhere. With more info, I can convince more of my people to join the cause. A lot of us are sick and tired of the way the AngloZionists are messing up the world, and with more knowledge of the powerful, incisive type provided by behind-the-news, we’ll be a lot more empowered to fight the evil in this world.

Pls keep up the great work :))!!